Vaccines are one of the most powerful tools for protecting herd health. Unlike antibiotics, which kill or inhibit bacteria after infection, vaccines teach the immune system to recognize a threat before it causes disease.

When you vaccinate cattle, sheep, or goats, you expose them to a harmless version of a pathogen so their immune system forms antibodies and memory cells. If the real pathogen arrives later, these memory cells trigger a rapid response and limit illness.

In an era of global trade and growing demand for animal protein, livestock farmers and veterinarians need evidence‑based vaccination programs to safeguard animal welfare, public health, and profitability. This guide covers all the aspects of livestock vaccines that will enable farmers and ranchers to take care of their cattle with complete awareness.

How Livestock Vaccines Work and Why We Vaccinate?

When an unvaccinated animal encounters a pathogen, it can take 7–14 days for its immune system to mount a sufficient antibody response. During that time, the pathogen replicates unchecked, often leading to severe disease or death. A properly vaccinated animal already has circulating antibodies and primed memory cells; its immune system can respond within about 48 hours.

This rapid response reduces fever, tissue damage, and pathogen shedding, protecting both the individual and the herd. Vaccination reduces the severity and duration of disease but seldom provides absolute immunity. Although the pathogens may still infect vaccinated animals, the clinical signs are milder and recovery is faster.

Natural vs. Vaccine‑induced Immunity

Natural and vaccine‑induced immunity both depend on exposure to antigens, yet vaccines are designed to be safer than uncontrolled infection. Modified‑live vaccines (MLV) stimulate both antibody and cell‑mediated immunity, while killed vaccines rely on adjuvants and require booster doses to produce strong antibody responses.

However, vaccine efficacy is influenced by management: poor storage, administering doses too close to the presence of maternal antibodies, or vaccinating sick or stressed animals can blunt the immune response. For producers, a sound vaccination program is an investment in biosecurity and animal welfare, reducing the risk of outbreaks and avoiding the losses seen with diseases such as FMD.

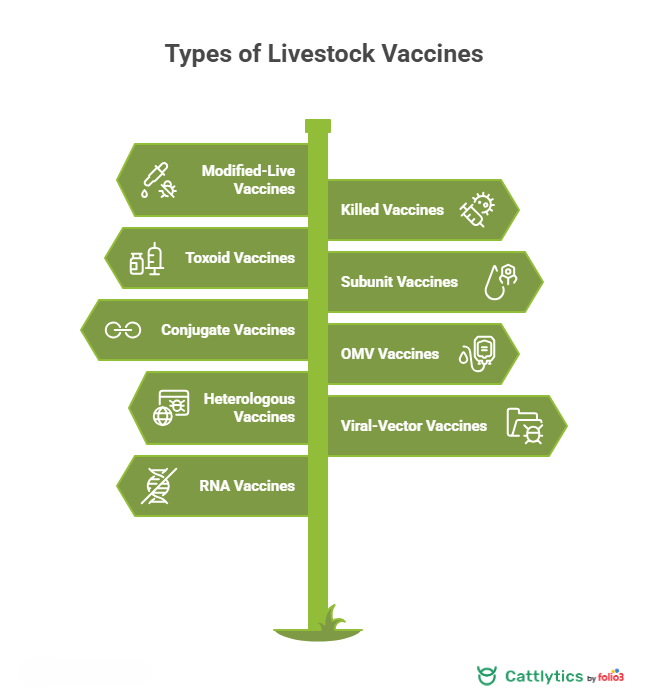

Types of Livestock Vaccines

Vaccines for cattle and other livestock fall into several categories. Understanding the differences helps you and your veterinarian choose the best products for your herd.

Modified‑live vs. Killed/inactivated Vaccines

Modified‑live vaccines (MLV) contain live organisms that have been weakened so they can replicate without causing disease. Once injected, they stimulate both antibody and cell‑mediated immunity. MLV products often offer broad, long‑lasting protection, but they must be handled carefully. Reconstituted MLVs should be used within a few hours and are not recommended for pregnant cows unless those cows were previously immunized with the same product.

Killed (inactivated) vaccines use organisms that have been chemically destroyed. They cannot replicate, making them safer for pregnant or immunocompromised animals. However, killed vaccines rely on adjuvants to stimulate the immune system and usually require a booster dose three to four weeks after the initial shot. Some commercial products combine MLV and killed components to broaden protection.

Toxoid, Subunit, and Recombinant Vaccines

Toxoid vaccines are prepared from inactivated toxins rather than whole organisms. Vaccines against tetanus and blackleg use toxoids to generate antitoxin antibodies that neutralize harmful toxins.

Subunit and recombinant vaccines include only specific proteins or antigens; for example, a viral surface protein expressed in a harmless yeast cell.

Conjugate vaccines link bacterial polysaccharides to proteins to enhance immune recognition. These newer technologies provide targeted immunity with fewer side effects but may be more costly.

Advanced Vaccines for Cattle

Vaccine research is advancing rapidly and here are the ones that getting noticed among the herd health professionals:

Outer‑membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccines harness naturally shed bacterial membrane fragments that carry multiple antigens.

Heterologous (Jennerian) vaccines use a mild relative of the target pathogen to stimulate immunity.

Viral‑vector vaccines insert genetic material from a pathogen into a harmless virus, prompting the host to produce the antigen.

RNA (mRNA) vaccines deliver messenger RNA encased in lipid nanoparticles; host cells translate the RNA into a viral protein, triggering immunity.

Core Vaccines and Diseases by System of Livestock

Livestock vaccines are often grouped by the body system they protect. Core vaccines target diseases with high prevalence or severe impact; optional vaccines are used when regional risk is high.

Respiratory Diseases

The bovine respiratory disease complex is a leading cause of morbidity in cattle. Viral pathogens include infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR), parainfluenza 3 (PI3), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), and bovine viral diarrhea (BVD). Secondary bacterial infections with Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni worsen pneumonia.

Moreover, Commercial respiratory vaccines typically combine these viral antigens and may include an M. haemolytica toxoid. Vaccinating calves two to three weeks before weaning and boosting them after weaning reduces the risk of respiratory disease outbreaks.

Reproductive Diseases

Reproductive vaccines protect unborn calves and maintain fertility. IBR and BVD viruses can cause infertility, abortions, and persistently infected calves. Bacterial diseases such as Leptospira spp. and Campylobacter fetus (vibriosis) also threaten reproduction. Cows and heifers should receive a 5‑way leptospirosis vaccine and vibriosis vaccine before breeding.

Meanwhile, open cows can be vaccinated with an MLV product four to six weeks before breeding, but pregnant cows should receive a killed vaccine or be vaccinated well before conception. Bulls should be tested for venereal diseases and vaccinated if recommended by a veterinarian.

Clostridial & Other Diseases

Clostridial diseases are caused by soil‑borne bacteria that produce deadly toxins. Blackleg (Clostridium chauvoei), redwater (C. haemolyticum), and tetanus (C. tetani) can kill animals suddenly. A 7‑ or 8‑way clostridial vaccine covering these and other Clostridium species is typically administered to cows, heifers, and calves. Optional vaccines may target pinkeye, scours, anaplasmosis, or Histophilus somni, depending on regional prevalence and veterinary advice.

Vaccination Schedules by Livestock Group

No single schedule suits every herd. Timing depends on the animal’s age, reproductive status, and management goals. Good nutrition, low stress, and proper handling are essential because vaccination does not equal immunization. The table below presents an example schedule for beef cattle; consult your veterinarian to adapt it to your situation.

| Livestock group & stage | Core vaccines & purpose | Timing (example) | Considerations |

| Cows & bulls – 4–6 weeks pre‑breeding | Viral respiratory vaccine (IBR, BVD, PI3, BRSV) plus 5‑way leptospirosis; include Campylobacter (vibriosis) vaccine if using natural service. A 7‑ or 8‑way clostridial vaccine is recommended for younger cows and bulls. | Give vaccines four to six weeks before breeding; use an MLV product only if cows are open; switch to a killed vaccine if cows are already pregnant. | Consider a breeding soundness exam for bulls and deworming animals during this period. |

| Open heifers – ≥6 weeks pre‑breeding | Same viral respiratory and leptospirosis/vibriosis vaccines as cows; MLV products are preferred for heifers. A 7‑ or 8‑way clostridial vaccine should also be given. | Vaccinate at least six weeks before breeding. If less time remains, use a killed vaccine and follow up with a booster. | Heifers have high nutritional demands; deworm and provide mineral supplementation. |

| Calves – 1–3 months old | 7‑way clostridial vaccine to jump‑start immunity. Optional intranasal respiratory vaccine for IBR/PI3/BRSV; pinkeye vaccine and deworm as needed. | Administer during early calfhood (1–3 months). | Do not give blackleg vaccine at birth; combine with dehorning, castration, and tagging. |

| Calves – 2–3 weeks pre‑weaning/post‑weaning | Killed or MLV viral respiratory vaccine with booster; Mannheimia haemolytica toxoid or combination MLV + toxoid; deworm and administer 7‑/8‑way clostridial vaccine if due. | Give the first dose two to three weeks before weaning and a booster after weaning. | Check marketing programs (e.g., preconditioned sales) for required vaccines and withdrawal periods. |

| Cows after weaning | Pregnancy check and cull open cows. Administer a scours vaccine one to three months before calving. Provide a leptospirosis booster if it is a persistent problem. | Mid‑gestation or post‑weaning. | Address other health issues such as eyes, udder, and hooves. |

Administration Methods and Techniques to Apply Livestock Vaccines

Correct administration is essential for vaccine efficacy and carcass quality. Always restrain cattle in a chute to minimize movement and prevent accidental injuries.

Injection Methods

Subcutaneous (SubQ) injections deposit the vaccine just under the skin. They should be given in the neck’s safe zone with the needle inserted at a 45‑degree angle. SubQ injections are generally less irritating and are preferred when the label allows.

Intramuscular (IM) injections must also be placed in the neck; insert the needle at a 90‑degree angle into the muscle. Use the smallest gauge needle that can effectively deliver the product: 20‑ to 18‑gauge, 1‑inch needles for calves under 500 lb and 18‑ to 16‑gauge, 1–1.5 inch needles for cattle over 500 lb. Do not inject into the hindquarters or rump, which damages expensive cuts of meat.

Aseptic Technique and Handling

- Good hygiene prevents injection‑site lesions and contamination.

- Change needles every 10–15 injections or sooner if they become bent or dull.

- Inject through clean, dry skin and use quality disposable needles.

- Never reuse a dirty needle in a vaccine vial; bacteria and debris can contaminate the bottle.

- Keep equipment clean and label syringes to avoid mixing up different products.

- Space multiple injections at least a hand’s width apart and limit the volume at a single site to 10 mL.

Dosage Accuracy & Record Keeping

Use syringes designed for the correct dose and confirm that multi‑dose syringes deliver accurate volumes. Keep comprehensive records: for each animal, note the date, vaccine name, batch number, dose, route, and withdrawal time. Accurate records support traceability, help diagnose potential vaccine failures, and are required for many quality‑assurance programs.

Vaccine Storage, Handling, and Biosecurity

Vaccines are fragile biological products; mishandling them is a common cause of apparent vaccine failure. Always purchase vaccines from reputable suppliers, check expiration dates, and plan to use them before they expire.

Transport & Storage

Transport vaccines in rigid coolers with ice packs and keep them out of sunlight. At home, store vaccines in a refrigerator between 35 °F and 45 °F (2 °C–7 °C). Avoid freezing; freezing kills the adjuvants in killed vaccines and can release toxins. Old refrigerators in barns often fluctuate outside the recommended range; use a thermometer or data logger to monitor temperature.

Equipment & Mixing

Use clean syringes free of disinfectant residues to avoid deactivating vaccines. Mix only what you will use within one to two hours; reconstituted MLV vaccines degrade quickly. During use, keep vaccine bottles and syringes in a small cooler to maintain temperature. Shake inactivated and toxoid vaccines gently before and during use, and discard any product that has frozen, overheated, or become contaminated.

Biosecurity and Disposal

Vaccination should be part of a broader biosecurity plan. Quarantine new arrivals for two to four weeks, vaccinate them according to veterinary advice, and prevent cross‑contamination by using dedicated footwear and equipment for different pens. Dispose of used needles in approved sharps containers and follow state or provincial regulations for discarding vaccine bottles. Never reuse reconstituted MLV vaccine after it has expired; discard unused portions after the session.

Economic Considerations and the Livestock Vaccines Market

Vaccines cost money, but disease outbreaks cost far more. On individual farms, pneumonia or abortion storms reduce weight gains, milk yield, and reproductive efficiency. Preventive vaccination helps avoid veterinary bills, drug costs, and lost production.

Market analysts forecast strong growth in the livestock vaccines sector as demand for animal protein rises and producers adopt preventive health programs. Research estimates that the global animal vaccine market was worth about US$17 billion in 2024 and may exceed US$44 billion by 2034, growing at roughly 10 % per year, with the livestock segment accounting for more than 70 % of revenue and North America contributing around 27% of sales.

New technologies such as viral‑vector and mRNA vaccines are attracting investment, although none are currently licensed for cattle. Producers should balance the cost of vaccines against potential losses, considering local disease prevalence, marketing requirements, and the value of animals. Consulting a veterinarian helps select cost‑effective vaccines and schedule boosters when immunity wanes.

Challenges, Myths, and Vaccine Efficacy

Myth-busting reality: mRNA technology in animal health is still under research; no mRNA vaccines are approved for cattle. They do not alter an animal’s genetic code; instead, they train the immune system to recognize and fight specific pathogens.

Voluntary vaccination: Most programs for vaccines in livestock are voluntary, designed around each operation’s risk–benefit analysis considering disease exposure, herd health, and market requirements.

Why vaccines may appear to “fail”:

- Improper storage or handling (temperature abuse or expired doses).

- Vaccination timed poorly against maternal antibodies in young calves.

- Animals under stress, malnutrition, or illness may not mount complete immunity.

- Use of mismatched vaccines for livestock that don’t match local pathogen strains.

Good practice: Always monitor animals for post-vaccination reactions and consult a veterinarian promptly if complications arise.

Developing a Herd‑specific Vaccination Protocol

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to vaccines in livestock. Effective protocols depend on herd size, management style, climate, and disease pressure.

Veterinary collaboration: Work with your vet to design a plan using the cattle vaccines list appropriate for your region, e.g., IBR, BVD, BRSV, Leptospirosis, and Clostridial diseases.

Timing and coordination: Align vaccines for cattle with breeding, calving, and weaning cycles. Synchronizing shots around low-stress periods improves immune response and reduces performance loss.

Health foundations: Adequate nutrition, parasite control, and stress reduction are essential for strong vaccine efficacy. Even the best beef cattle vaccines won’t perform well if animals are nutrient-deficient or immunocompromised.

Record keeping: Maintain logs of vaccination dates, batch numbers, and administration routes to track effectiveness and meet market certification needs (e.g., preconditioned sales).

Annual review: Revisit your herd protocol yearly to adapt to disease trends, regional outbreaks, or newly available vaccine technologies. Continuous evaluation ensures sustained herd immunity and better returns on investment.

Conclusion

Vaccination is a cornerstone of livestock health and profitability. It primes the immune system so animals respond rapidly to pathogens, reduces disease severity, and prevents costly outbreaks. To capture these benefits, producers must choose appropriate vaccine types, handle and administer them correctly, and develop herd‑specific protocols in consultation with veterinarians. Emerging technologies like viral‑vector and RNA vaccines may soon expand options, but for now, the fundamentals remain the same: combine vaccination with good nutrition, stress reduction, and biosecurity to safeguard animal welfare and farm profitability.

FAQs

How Often Should Cattle Be Vaccinated?

The vaccination schedule varies based on your herd’s age group, disease exposure risk, and management system. Most beef cattle vaccines are given once a year or timed with key herd events like breeding, calving, or weaning. Always work with your veterinarian to create a schedule that fits your operation’s needs.

Why Do Vaccines in Livestock Sometimes Fail?

When vaccines appear ineffective, it’s often due to preventable issues such as improper storage, poor timing, or vaccinating animals that are already stressed or unwell. Using a vaccine that matches the disease strains circulating in your area and following proper handling practices helps ensure stronger protection.

What Is the Best Time to Vaccinate Beef Cattle?

Timing vaccinations correctly is critical for immunity. The best periods are usually before breeding, branding, or weaning, when cattle experience lower stress. Administering beef cattle vaccines during calm handling conditions supports better immune response and long-lasting protection.

Can Vaccinated Livestock Still Get Sick?

Yes, vaccination reduces the risk of severe illness, but it doesn’t guarantee complete immunity. Animals under high disease pressure, nutritional stress, or exposed to outdated vaccines may still show mild symptoms. However, vaccinated herds experience fewer outbreaks and recover faster overall.

What Records Should I Maintain After Vaccinating Livestock?

Accurate record keeping is essential. Track details like vaccine name, batch number, dosage, date, animal ID, and the person administering it. These records strengthen traceability, simplify audits, and help monitor herd health and vaccine performance over time.