Lameness in cattle is a sign of pain or injury, not a disease itself. It indicates something is wrong in a hoof, joint, or limb. It is very common: surveys find roughly 10–50% of cows go lame during their lifetime, and even 20–30% of market cattle arrive with lameness. When a cow goes lame, she limps, eats less, and produces less milk or gains less weight.

In dairies, one analysis found that treating a lame cow costs about $90–$400 in veterinary care and lost milk. In beef cattle, lameness slows growth. Lame steers may need two extra weeks to finish, and auctions often discount lame animals. Lameness also raises culling rates, as at least 10% of culled cows are lame.

Because of these welfare and economic impacts, early detection and treatment are essential to protect herd health and profits. In this guide, you’ll learn how to recognize and respond to lameness quickly, keeping your cattle sound.

What is Lameness in Cattle?

Lameness means a cow is walking abnormally due to pain or dysfunction in a leg or hoof. It is a clinical symptom, not a disease itself, but rather an indicator of various common cow diseases affecting hoof and limb health. Many factors often combine to cause lameness, so careful examination is needed. In fact, over 90% of cattle lameness cases originate in the hoof or claw.

Types of Lameness in Cattle

Common types of lameness include:

Infectious hoof diseases: Bacterial hoof infections are major culprits. Foot rot (interdigital necrobacillosis) causes sudden swelling and a foul smell in one foot. Digital dermatitis (hairy heel wart) produces painful ulcerative lesions on the heel bulbs of the hind feet. Both are spread in manure and require prompt treatment. Viruses can also attack hooves: for example, Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) causes a hairy-wart syndrome in a few percent of cases.

Claw-horn lesions: Non-infectious hoof problems like sole ulcers, white-line disease, and laminitis fall here. Laminitis often follows acidosis or mineral imbalance, leading to separated or bruised hoof horn. These horn defects build up slowly and cause chronic limping.

Limb and joint injuries: Trauma can hurt any leg joint or tendon. Fractures, sprains, or arthritis, including septic joint infection, produce obvious limping. Also consider back or pelvic problems: cows may “fake” a limp due to hip or spine pain. Any injury or defect in the limb structure is included here.

Clinical Symptoms of Lameness in Cattle

Observe how cows move and stand. A lame cow will look different: she may shorten her stride, favor one leg, shuffle, or arch her back. You might see uneven weight-bearing or a slower, hesitant walk. Lame cows often lie down more and spend less time eating.

Because cattle tend to mask pain, even subtle gait changes count; small limps or a slightly uneven stance should not be ignored. Also, watch cows anytime they walk briskly, like they exit the milking parlor or approach the feed bunk, since limps can be easier to spot then.

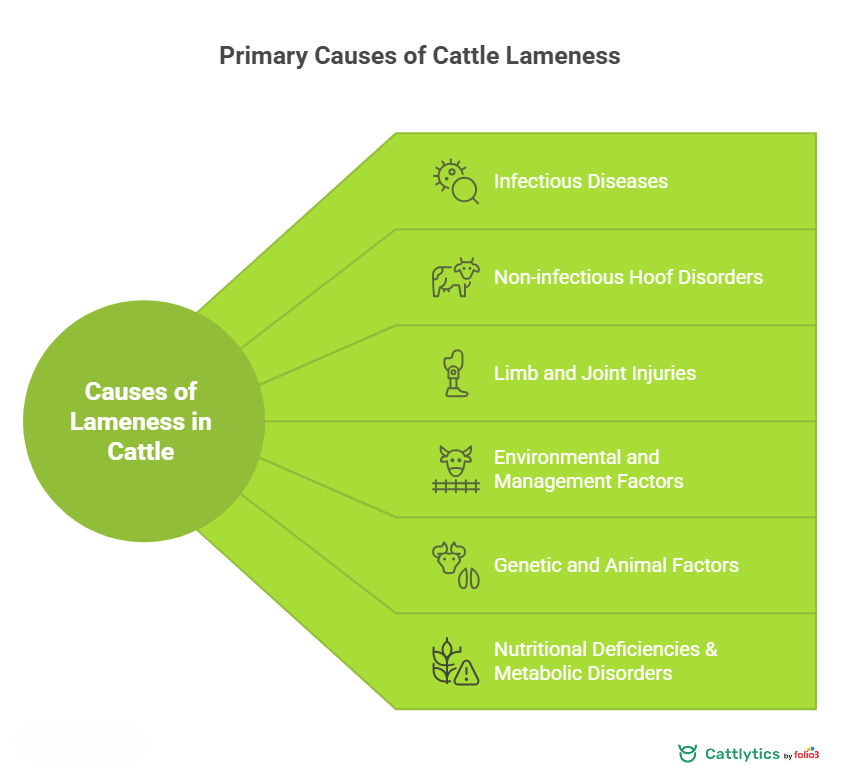

Causes of Lameness in Cattle – Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors

Lameness in cattle arises from a combination of diseases, injuries, and environmental factors. Key causes include:

Infectious Diseases

Foot infections are a common lameness. Foot rot (interdigital necrobacillosis) is the classic example. It is a bacterial infection that causes sudden, painful swelling between the claws; it thrives in mud or manure. Foot rot alone accounts for up to 20% of diagnosed lameness.

Meanwhile, digital dermatitis (hairy heel warts) is another highly contagious infection causing ulcerative lesions at the heel. These lesions hurt badly and recur unless managed. Even some viruses can cause lameness, like BVDV, which can produce “hairy heel” lesions in a few percent of cows. Rapid treatment and hygiene, like foot baths and isolation, are needed to stop the spread.

Non-infectious Hoof Disorders

Many hoof lesions are not bacterial. Laminitis is an example, an inflammation of the hoof laminae typically triggered by high-concentrate diets or metabolic stress. Laminitis makes the hoof sole and wall separate slightly, leading to soft spots, bruises, or sole ulcers. Other non-infectious problems include white-line disease (hoof wall cracks) and corkscrew claw (twisted feet). These often start from uneven wear, poor trimming, or poor horn quality. All these cause chronic or recurrent lameness as the claw structure fails.

Limb and Joint Injuries

Trauma to legs or hooves is common. Stepping on nails, sharp stones, or metal can puncture a foot and cause abscesses and hoof bruises from uneven footing, causing pain. Cows may also suffer fractures, sprains, or joint infections (septic arthritis) from slips or fights. Such injuries can cause severe limps. Back, pelvis, or nerve injuries are rarer but can mimic lameness by producing an abnormal gait.

Environmental and Management Factors

The barn and pastures you provide greatly influence lameness. Hard or abrasive floors of bare concrete without mats or grooves dramatically increase hoof wear. Cows standing too long on bare concrete press down on their claws. Muddy, wet, or manure-packed pens soften hoof skin and spread bacteria, promoting foot rot and dermatitis.

Moreover, slippery or uneven surfaces cause slips and strains. In cold climates, ice or frozen ground can crack hooves. Good management, such as soft bedding, clean dry alleys, and rubber mats on high-traffic lanes, helps prevent these environmental risks.

Genetic and Animal Factors

Some cows are simply more prone to lameness. Genetics play a role: hoof shape and horn quality are inheritable. Breeds or lines selected for heavy milk or meat often pay for it with weaker feet. Also, age and body condition: older cows and obese cows have thinner soles and more hoof pressure. Rapid growth in calves can cause joint deformities in the future. Over time, culling consistently lame animals and breeding from sound-footed stock tracked through cow-calf software will lower your herd’s risk.

Nutritional Deficiencies & Metabolic Disorders

What and how you feed matters for hooves. Diets very high in fermentable carbohydrates (grains, silage) can cause subacute acidosis in the rumen, which leads to laminitis in the hoof. In other words, a “sour” rumen can inflame the claw. To prevent this, always feed enough adequate fiber and change rations gradually. Deficiencies of key minerals also hurt hoof horn: zinc, copper, selenium, and biotin are vital.

Early Detection Techniques for Diagnosing Lameness in Cattle

Early detection pays off through cattle health monitoring systems. Cows recover faster and cheaply if lameness is caught early. In herds without routine screening, farmers often detect only 20–40% of lame cows. Lameness also tends to spike around calving, so watch fresh cows closely. Follow a systematic check protocol:

Visual Locomotion Scoring

Observe cows walking on a flat, non-slip surface as they exit the parlor. To make detection systematic, use a locomotion scoring system.

- Have cows walk 4–6 strides on a level, non-slip surface.

- Score each cow on a 1–5 scale (1 = sound, 5 = severe limp).

- A score of 2 might mean a slight limp or arching, while 4 is a pronounced limp.

- A 1–5 locomotion score is now standard practice on dairy farms.

Keep score records for each cow, so you notice if a cow’s gait worsens over time. Always watch cows whenever you can, as they come to the bunk or water because a cow might limp only under certain conditions.

Physical Examination

When you identify a cow as potentially lame, examine her carefully. Restrain the cow in a headlock or chute. Clean off the foot and trim any overgrown horn. Inspect the sole, heel, interdigital space, and coronary band for wounds, swelling, or foreign objects. Use hoof testers (plier-like clamps) to press on different parts of the foot; pain response pinpoints the sore area. Check palpate joints and tendons for heat, swelling, or crepitus. Don’t forget to check the other feet and the cow’s overall posture. A thorough foot-and-leg exam will usually identify the cause of the limp.

Data and Recording

As you diagnose each case, record everything. Log the cow’s ID, date, locomotion score, and diagnosis, along with treatments given using the cattle management system for centralized tracking. Many farmers use herd software or spreadsheets to track this. These records help you see if certain pens or diets correlate with lameness events, or if specific cows have chronic issues. Good record-keeping is part of a control program: it ensures no cow slips through the cracks and lets you measure progress.

Veterinary Assistance

Involve your vet when needed. If a case is not improving after 3–4 days of treatment, have the vet re-examine. Also get professional help for complicated or severe cases: for example, deep puncture wounds into joints, suspected fractures, or outbreaks of a contagious hoof disease. The vet can perform advanced diagnostics like nerve blocks, imaging, culture of lesions, and guide treatment. Remember that lameness is a clinical sign; the underlying cause may be subtle. Vet input is key to solving tough cases.

Viable Options for Treatment of Lameness in Cattle

The faster you treat lameness, the better the outcome. The general approach is: clean, trim, treat pain, treat cause. A veterinarian should be consulted in complex cases, but many treatments can be done on-farm:

General First Steps

Isolate the lame cow on dry, comfortable bedding. Wash and trim the sore foot to expose the lesion. Administer an NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory) such as flunixin or meloxicam for pain and swelling. If a bacterial cause is likely, start antibiotics as prescribed by your vet. Always follow label/vet instructions and observe drug withdrawal times. Early action prevents the problem from worsening.

Foot Rot (interdigital necrobacillosis)

This responds very well to prompt treatment. Trim and clean the foot thoroughly. Give a broad-spectrum antibiotic like long-acting penicillin or oxytetracycline and an NSAID. Keep the cow standing on dry bedding. Most foot rot cases recover fully if treated within 1–2 days. If the cow shows no improvement after 3–4 days, have the veterinarian reassess.

Digital Dermatitis (hairy heel wart)

Clean the lesion and apply a topical antibiotic solution such as oxytetracycline spray or a tetracycline bandage. You may soak a clean wrap in medication and secure it for 1–2 days while continuing NSAIDs for comfort. Footbaths are essential for this disease: using 2–5% copper sulfate or 5–10% zinc sulfate solutions regularly will kill the responsible bacteria and prevent spread. With treatment and footbath use, most warts heal in a few weeks.

Toe Tip Necrosis (dewclaw infection)

Trim away the dead dewclaw tissue and clean the area. Treat it just like foot rot: apply antibiotics and NSAIDs, and keep the foot dry. Isolate the cow on clean bedding. These infections usually heal well with prompt care.

Joint Infections & Arthritis

If lameness comes from a joint or tendon sheath, it usually needs aggressive vet treatment. A septic joint often requires flushing (lavage) and high-dose antibiotics, sometimes injected into the joint after cleaning. Give tetanus antitoxin if a deep wound is present. Stall the cow and continue systemic antibiotics and NSAIDs. Note that severe joint injuries or infections can be complicated to cure; in hopeless cases, culling may be the most humane choice.

Laminitis

Treatment is aimed at removing the cause. If acidosis (grain overload) is suspected, immediately cut back on grains and increase good forage while using NSAIDs for inflammation. Paring the hoof to reduce pressure points and providing soft bedding are key. Confine the cow and limit standing time. Acute laminitis often responds to this care, but chronic laminitis may not recover fully; chronically lame cows may need to be culled to avoid ongoing pain.

Non-infectious Injuries

These are typically managed mechanically. If a foreign object (nail, stone) is embedded, remove it and flush the tract with antiseptic. Trim off any loose or bruised sole horn. Place a hoof block on the healthy claw to lift weight off the sore foot. If there is an abscess, lance it and bandage it. Sprains and minor fractures require stall rest on deep bedding and NSAIDs. If a fracture or tendon rupture is confirmed and the animal cannot walk, the outlook is poor, and humane euthanasia is the kindest option.

Pain Management

Always control pain aggressively. Approved NSAIDs should be given to reduce pain and swelling. Pain relief encourages the cow to bear weight and move, which actually helps healing. Local nerve blocks (lidocaine) can temporarily numb a foot for examination, but long-acting pain relief is usually needed for more than a day or two.

Supportive Care

In addition to treating the specific issue, provide comfort. Tie or stall the cow on thick, cushioned bedding, so she stands up less. Apply a hoof block or soft pad to unload pressure. Keep feed and water at head level so she doesn’t have to walk far. Change bandages or wraps daily, cleaning and re-packing wounds to prevent infection. Good supportive care improves recovery speed and cow comfort.

When to Cull or Euthanize

If a cow is not improving or is unable to bear weight after 1–2 weeks of treatment, consider humane euthanasia. For example, a deep joint or bone infection, or a severe fracture, often warrants culling rather than prolonged treatment. Work with your vet to set “stop points” like no improvement after X days. Timely, humane decisions protect animal welfare and prevent further losses.

Preventive Strategies to Avoid Lameness in Dairy Cattle

Prevention is better than a cure, and avoiding common herd health management mistakes is the first step to reducing lameness in your operation. A combination of good facilities, care, and management keeps hooves healthy:

Housing & Flooring

Provide comfortable, non-slip footing. Use deep, clean bedding like sand, straw, or rubber mattresses in stalls. In walkways and feed alleys, rubber mats or grooved concrete give better traction and reduce hoof wear. Avoid bare concrete wherever cows stand. Ensure pastures and loafing areas are well drained, as mud invites foot rot. Also, design stalls to proper dimensions, so cows can stand and lie without stepping awkwardly. Good barn ventilation and cooling reduce heat stress, encouraging cows to lie down rather than stand on hard floors.

Foot care & Hoof trimming

Schedule and track hoof trimming with cattle task management tools to ensure hooves are trimmed at least once per year. A trained hoof trimmer can restore proper angles and relieve pressure points, preventing sole ulcers and cracks. In problem herds, twice-yearly trimming may be needed. For infectious diseases, regular footbaths are a key control. A properly concentrated footbath after milking can kill pathogens like digital dermatitis. When trimming or treating a lame cow, attach a hoof block to the healthy claw to help her offload the sore foot. Routine hoof care and footbaths are cornerstones of lameness prevention.

Nutrition Management

Balanced diets support hoof health. Ensure cows get enough fiber (forage) so rumen pH stays stable, as it prevents acidosis/laminitis. Use testing to confirm adequate effective fiber in TMR. Avoid sudden ration changes. Supply all needed minerals and vitamins: supplements should include zinc, copper, selenium, and biotin, which strengthen hoof horn. Maintain cows at a moderate body condition: too thin cows have weak soles, and too-fat cows strain joints. Work with a nutritionist to fine-tune rations for hoof health.

Hygiene & Biosecurity

A clean environment breaks disease cycles. Scrape and clean alleys multiple times daily so cows are not forced to stand in manure. Keep stalls and bedding dry. Disinfect hoof-trimming and handling equipment between animals. Use targeted footbaths for high-risk groups like fresh cows or postpartum heifers on a regular schedule. Remember that some hoof problems have systemic causes: include BVDV vaccination in your herd health plan, since BVD can cause viral hoof lesions. Footbaths and vaccinations together help prevent infectious lameness.

Stockmanship & Handling

How you move cows affects lameness risk. Handle cattle calmly and quietly. Never crowd or rush them on slippery surfaces; use well-designed alleys and chutes for easy movement. Low-stress handling with patience and proper use of gates to prevent slips and bruises. Train all workers in gentle methods, as cows get more lame from stress and panic than from slow walking. Avoid electric prods, especially on lame cows; it only makes them run and worsens the injury. Good stockmanship with quiet moving and solid footing keeps feet safer.

Breeding & Genetics

Since hoof traits are partly inherited, select for sound feet. Use bulls and replacement heifers from lines known for hoof health. Include claw health or lameness traits in your breeding index if available. Over generations, breeding for good hoof angles, strong hoof horn, and correct leg structure will reduce lameness rates. In commercial dairy farms, some producers also crossbreed dairy cows with robust beef bulls to improve foot quality. Always inspect feet on new genetics: cull replacements with chronically poor hooves.

Monitoring & Record Keeping

Prevention programs need data. Record every lameness event, along with the cow’s locomotion score, lesion, and treatment outcome. Use dairy management software or simple charts to tally cases by barn, pen, or diet group. For instance, if you see multiple cases in one pen, check that pen’s flooring or bedding. Many dairies set a lameness goal and track it. Analysis of your data lets you refine management, like changing stall mats if lameness rises when new cows calve. Consistent monitoring and records help you catch problems early and fine-tune your herd health plan annually.

Step-by-Step Early Detection and Treatment Plan for Cattle Lameness

This step-by-step plan helps you quickly spot early lameness, make confident on-farm decisions, and treat affected cattle before the problem becomes costly or severe.

- Routine monitoring: Observe your herd walking whenever possible with cattle monitoring assistance. Score locomotion (1–5) on a flat surface at least monthly. Note any cow with a score ≥2 and flag her for closer examination.

- Initial assessment: When you spot a limp, gently separate that cow for inspection. Watch her walk a few strides again and see which leg she is favoring. Decide if the lameness is new or has been developing. Handle her calmly to avoid panic.

- Physical examination: Restrain the cow in a chute or headlock. Clean and trim the suspect hoof, then inspect it closely. Use hoof testers (pliers) to apply pressure on the sole and heel; the cow’s reaction will pinpoint the sore area. Examine joints and tendons for heat or swelling. A thorough foot-and-leg exam usually reveals the cause.

- Record findings: Write down the cow’s ID, date, locomotion score, and your diagnosis using cattle lifecycle records management to maintain comprehensive health histories. Include details as Left hind sole ulcer – trim + block + oxytet. Good records track treatment success and reveal any recurring problems or hot spots in the herd.

- Intervention: Treat the cow immediately and trim off loose or damaged hoof horn. Apply a hoof block to the healthy claw if it will relieve pressure. Administer antibiotics or topical therapies if an infection is present. Clean any wounds and bandage them. Give an NSAID for pain/inflammation. Early and decisive treatment prevents the lesion from worsening.

- Follow-up: Check the cow daily. Re-examine and re-score her hoof every 2–3 days. Change bandages and reapply treatments as needed. If there is no improvement in 3–4 days, have your veterinarian re-evaluate the cow. Continue supportive care until the cow is walking normally again.

- Review management: After the cow recovers, ask why she went lame. Was there a feed change, a rough patch in the pen, or a stall issue? Address the root cause if possible and train the staff accordingly to recognize lameness signs early. Make these steps part of your standard routine, as consistency in monitoring and treatment is key to prevention.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Lameness in cattle is both a welfare concern and a costly production issue. Even mild cases reduce milk yield, weight gain, and fertility, making early detection essential for your herd’s performance. While good flooring, hoof care, nutrition, and hygiene remain the foundation of prevention, you gain a significant advantage when you pair these practices with cattle health monitoring technology. Continuous behavior and activity tracking help you spot subtle gait changes long before they become severe, allowing faster, more effective treatment.

Ready to reduce lameness in your herd and catch mobility issues before they become costly? Consult with our experts at Cattlytics to explore how you can gain real-time alerts, early lameness detection, and actionable insights to protect your herd’s productivity and welfare by building a cattle health monitoring system.

FAQs

What Is the Most Common Cause of Lameness in Cattle?

Most lameness starts in the feet, and in around 70–90% of cases, comes from hoof problems. The major issues include infectious conditions like Digital Dermatitis and Foot Rot, along with non-infectious lesions such as sole ulcers, white line disease, and bruising.

What Is the 90-90-90 Rule for Cattle Lameness?

The 90-90-90 rule is a simple guideline suggesting that most lameness occurs in the feet, primarily in the hind limbs, and usually in the outer claw. While not perfect, it helps farmers and vets narrow down where to start looking.

How Does Lameness Impact Milk Production and Growth?

Lameness quickly reduces a cow’s ability to eat, move, and perform, leading to noticeable drops in milk yield, lower weight gain, poorer fertility, and a higher chance of culling. The pain and reduced mobility directly cut into overall farm productivity.

Can Cattle Lameness Be Detected Early With Technology?

Yes. Modern monitoring systems can spot early behavior changes such as reduced activity or altered movement, days or even weeks before you’d notice them visually. This gives you a crucial head start on treatment and recovery.